| |

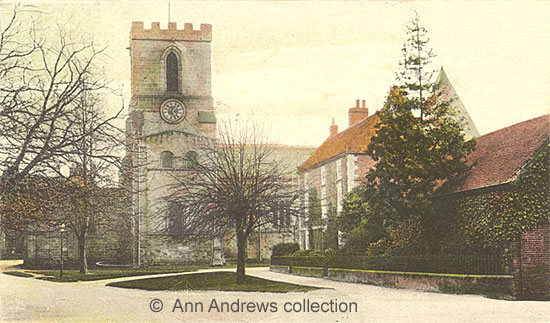

| Melbourne Parish Church, St. Michael and St. Mary |

Photograph by Richard Keene, 1877.

|

In recent years Simon Jenkins included just two Derbyshire churches in his top hundred, awarding them both four stars[1].

Melbourne was one and St. Oswald's at Ashbourne the other. It is not hard to see why he rated them both so highly. It is Grade I listed today.

Rev. Joseph Deans, writing in the 1850s as the church was about to undergo some much needed restoration, stated that tradition referred to a church

being first erected in the 7th century by Ethelred "on account of the violent death of his Queen" (Osthryth). He added that

the building either fell into decay or was destroyed by the Danes, possibly in the ninth century and the present church was then built on the

site[2]".

The present Melbourne Church is cruciform in shape and was built in the 11th century, so belongs from the early Norman era of church architecture.

The Domesday book mentions "a priest and a church, and one mill of three shillings, and 24 acres of meadow land" on the royal manor here.

In 1133, when Henry I founded the bishopric of Carlisle, one of the first endowments was to Melbourn church[3].

Deans believed that originally there were no windows in the outer walls of the nave, with all the light coming through the clerestory windows instead.

The roof at the west end was roofed with flat pieces of sandstone, and it was supposed that the whole church was originally roofed in sandstone[2].

J. Charles Cox thought it "it is one of the finest and most interesting Norman churches in England" in 1877. He pointed out the resemblance

of the central tower to that of Norwich Cathedral, which dates from 1090[4], though the upper part is much

more recent. The photograph of the exterior, above, is also from 1877 and is from the frontispiece of one of his books on Derbyshire's churches[5].

Richard Keene's image provides some indications of what was originally here. For example, the chancel's roof line is considerably lower than it had

been in past centuries and this is clearly visible on the embattled lantern tower, where former windows (or doorways) are blocked up.

Similarly, the chancel and transept closest to the viewer show signs of the former apse[6]. The two small

towers at the west end, seen above covered with small spires or pinnacles that were twenty feet high, are capped today. They had been erected in Gilbert

Scott's time (see below) and were covered with slates. The western façade had never been properly completed[7],

so this would have been an attempt to resolve the problem. However, the spires were removed in 1955 and the stone parapet at the west end was then restored[8].

|

| 1918-19 |

The building was in a most "dilapidated and forlorn state by 1857"[13] and the church wished to raise £1200

for its restoration, with £300 already promised within the parish[2]. It was also hoped that Lord Palmerston and his

family would help[2]". Palmerston, twice Prime Minister (1855-8 and 1859-65), was married to the sister of both William

and Frederick Lamb, the 2nd and third Viscounts Melbourne respectively. Emily Palmerston (formerly Cowper, nee Lamb) had inherited Melbourne Hall following the death of

her brother Frederick in 1853.

In September 1858 a fete was held in Viscount Palmerston's gardens in aid of the restoration fund[9]. The

following year it was announced that a Bazaar was to be held in the grounds of the hall on 29th and 30th June. Amongst the patrons were The Countess of

Chesterfield, the Countess Cowper, Lady Palmerston and the Hon. Mrs Lamb[10].

The report of the architect Mr. George Gilbert Scott, in early 1859, was very honest. As well as noting the problem at the west end of the church,

"its eastern tri-apsydal termination was almost obliterated, its high-pitched roofs had been lowered, and several other of its features mutilated,

it still retains, particularly within, very much of its original nobleness of character ; and if restored, though but in a partial degree, would exhibit

them to greater advantage." He added that the repairs would be extensive.[7]

By late December it was anticipated that all the restoration Mr. Scott had considered necessary would be able to be completed. The work had been contracted

to Mr Hall, a Nottingham architect, and was underway. This contract included repairing the fine west doorway and both the exterior of the west end wall and

the lower part of its interior. The pillars, walls and chancel were to be restored; the transept and south aisle were to be re-roofed, the whitewash had to be

removed from the walls, the lantern tower was to be opened and there was to be reflooring and repewing. The church was then full of scaffolding, planks, beams,

stones and boards some of the repair work had already revealed items of interest[11].

Advertisements were placed in the press to announce that that the church was to re-open on Saturday 3 November 1860, having been closed for more than year[12].

It was now lit by 160 jets of gas, and the "warming had been executed by Rosser of London". An organ had been added and was to be used for the first time

at the opening service. During the restoration traces of fire damage had been discovered and it had also become evident that the nave had also been without a roof

for "a long series of Years". The church was now able to accommodate 6-700 people. One journalist was blunt, commenting that it "had previously been

a disgrace to the parish"[13].

Long before the service to re-open the church was to due start, the door was besieged by individuals wishing to gain admission and almost the minute the it was

opened the seats were filled[14].

|

| West end doorway - a fine example of Norman architecture |

The west door, shown in the two images (above and below) is truly impressive. It is centrally placed between the two west towers, the top of the southernmost

just visible on the top right of the photo. There are four orders of colonettes with both plainer and zigzag voussoirs (i.e. the wedge shaped stones that form the arch)

surrounding the door. A further pair of columns support the outer semicircular arch of larger stones. The window above was converted in the 15th century[6].

The gable above it is very shallow.

Although this doorway is no longer in everyday use it "opens into a spacious arch which leading to a portico extending the whole breadth of

the church and covered by a groined arch [12]."

|

Carvings above the West door's colonettes,

those above can be seen to the left of the door and those below on the right hand side. |

|

Early evening, Summer 2017.

The north transept, with its Norman windows. There are also five narrower Norman windows along the clerestory; the aisle windows

below are Perpendicular replacements [6]. The chancel is hidden behind the tree.

The twelfth century north door and the side of the nothern tower at the west end of the church. The doorway is similar to the one on the south side of the building,

though here the voussoirs are more elaborate [6]. There is a flat buttress below the aisle window on the left. Others, of

varying heights, can be seen elsewhere on the exterior of the church.

As someone wrote in 1886,

"Melbourne Church is, in fact, a Norman Cathedral. It is one of the most notable and beautiful in England. [15]"

It is a view others have shared both before and since.

|

The Church and War Memorial in Church Square, 1928.

Close House is the 18th early century red brick building on the right.

The vicarage can just be seen behind the church, on the left. It is "a stone, irregular building,

pleasantly situated with its garden on the south bank of the pool". Built in the spring of 1834

by the Rev. Joseph Deans, M.A.[16]. Both are Grade II listed. |

At the end of the war, like many other towns and villages throughout the UK, Melbourne faced the difficult job of deciding on a suitable

location for a war memorial[17]. The site eventually chosen was the grass plot near the church

and in May 1920 the unveiling and dedication took place.

Lord Walter Kerr performed the ceremony. The monument is made of Cornish granite, erected by public subscription, on which are all 88 names

of the men who fell in the war[18]. As can be seen from the photograph below, a further 20 names

were added at the end of the Second World War.

The WW2 names on the base of the memorial, including that of SPR. W. W. Hatton R.Eng

William Wallace Hatton, whose father was a casualty in WW1, was killed in France on 1 June 1940, aged 21.

He was the 4th cousin of the web mistress.

The name of his father Wallace is on the opposite side (see the next page for another memorial).

|

Images:

1. Melbourne Church (about 1877), Heliotype from photograph by R. Keene, by H. M. Wright and Co.. Plate I, Cox[5].

2. "The Church, Melbourne". Published by T. Warren, Melbourne, No.3. Posted Oct 1918 at Melbourne. © Ann Andrews collection.

3. "West Door, Melbourne Church, Derbyshire". Published by Joseph W Warren, Stationer and Picture Post-Card Repository, Melbourne, Derbyshire.

7. "Parish Church and Cenotaph, Melbourne". No publisher, but No.16065. Not used. A pencilled date on the card reads 16/8/28 - which could indicate

the date the card was bought.

Photographs (images 4, 5 and 6) are © Andy Andrews.

Photograph of the base of the war memorial (image 8) © Susan Tomlinson.

Written, researched by and © Ann Andrews.

Intended for personal use only.

|

References:

[1] Jenkins, Simon (1999) "England's Thousand Best Churches", Allen Lane, The Penguin Press,

Penguin Books Ltd., 27 Wright's Lane, London, W8 5TZ, England, ISBN 0-713-99281-6.

[2] "Leicestershire Mercury" 1 August 1857. Leicester Architectural and Archaeological Society - (annual meeting

and excursion).

[3] References to a church here at the time of the Domesday survey are from:

i. Cox, J Charles (1877) "Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire Vol III" Chesterfield: Palmer

and Edmunds, London: Bemrose and Sons, 10 Paternoster Buildings; and Derby, The Hundreds of Appletree and Repton and Gresley. Unfortunately,

Cox provided the wrong year for the completion of the restoration of the church, giving the year as 1862 instead of 1860.

ii. Domesday survey has been checked in other sources, too. See, for example, the link to The Domesday Book Online under

Useful sources.

[4] Cox, John Charles, (1915, 2nd edition, revised), "Derbyshire" - Illustrated by J. Charles

Wall, Methuen & Co., London.

[5] Also from Cox, J. Charles (1877). See reference [3] above.

[6] Pevsner, Nikolaus (1953), "The Buildings of England, Derbyshire",

Penguin Books.

[7] "Derby Mercury", 23 February 1859. Report to the restoration committee by Mr. Scott.

[8] "Derby Daily Telegraph", 8 September 1955. Down come those odd slated pinnacles. The

slates were said to be in a dilapidated condition.

[9] "Staffordshire Advertiser", 4 September 1858. Restoration of Melbourne Church.

[10] "Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal", 20 May 1859. Announcement that a bazaar would be

held in late June.

[11] "Leicestershire Mercury" 17 December 1859.

[12] "Derbyshire Courier" 3 November 1860. The Re-opening of Melbourne Church.

[13] "Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal", 2 November 1860. Melbourne Church.

[14] "ibid.l", 9 November 1860.

[15] "Derby Mercury", 24 November 1886.

[16] Briggs, John Joseph, F.R.S.L. (no date) "Guide to Melbourne and King's Newton, Derbyshire",

published London by Bemrose and Sons, Paternoster Row ; and Irongate, Derby. Also his "The history of Melbourne, in the county of Derby",

(1852).

[17] "Derby Daily Telegraph", 6 May 1919. War Memorial at Melbourne. Discussed in a Letter

to the Editor.

[18] "Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal", 28 May 1920. Melbourne. War Memorial Unveiled.

Melbourne is mentioned in the following on-site transcripts:

|

|

|